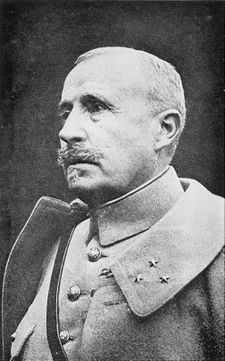

Robert Nivelle

| Robert Nivelle | |

|---|---|

| 15 October 1856 – 22 March 1924 | |

|

|

|

| Place of birth | Tulle, France |

| Place of death | Paris, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | French Army |

| Years of service | 1878-1921 |

| Rank | General de division |

| Commands held | 5th Artillery Regiment 27th Infantry Brigade 61st Reserve Infantry Division III Corps Second Army French armies on the Western Front French forces in North Africa |

| Battles/wars | Boxer Rebellion World War I |

| Awards | Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur Médaille militaire Croix de guerre 1914–1918 Distinguished Service Medal |

Robert Georges Nivelle (15 October 1856 – 22 March 1924) was a French artillery officer who served in the Boxer Rebellion, and the First World War. He took command of one of the main French armies engaged in the Battle of Verdun, leading it during its successful counter-offensives against the Germans, but was accused of wasting French lives during some of his attacks. He became Commander-in-Chief of the French armies on the Western Front in December 1916, and was criticised in that capacity for not exploiting good opportunities to attack the Germans. He was responsible for the Nivelle Offensive, which faced a very large degree of opposition during its planning stage. When the offensive failed to achieve a breakthrough on the Western Front, Nivelle was replaced as Commander-in-Chief in May 1917.

Contents |

Early life and career

Robert Georges Nivelle was born on 15 October 1856, in a French provincial town called Tulle in Corrèze. He was born to a French father and an English mother.[1][2] He begun his service in the French Army in 1878 after he graduated from the École Polytechnique that year. Starting as a sub-lieutenant with French artillery, Nivelle became a colonel of artillery in December 1913.[2] During that period, Nivelle served with distinction in Algeria, Tunisia, and China.[2] He was involved in the Boxer Rebellion in China.

First World War

Described as "an articulate and immensely self-confident gunner"[1], Nivelle played a key role in defeating German attacks during the Alsace Offensive, the First Battle of the Marne, and the First Battle of the Aisne, as a result of the intense artillery fire he organised against them.[2] Consequently, he was promoted to become a general in October 1914.[2] In 1916 the Battle of Verdun occurred (21 February – 18 December), during which Nivelle was a subordinate to Philippe Pétain.[3] When Pétain was promoted to the command of the French Central Army Group, Nivelle was promoted to Pétain's previous command of the French Second Army, which was fighting against the Germans at Verdun, and he took direct control of the army on 1 May 1916.[3]

Nivelle is considered to have squandered the lives of some of his soldiers in wasteful counter-attacks during the Battle of Verdun; only one fresh reserve brigade was left with Second Army by 12 June.[4] After Fleury was captured by the Germans on 23 June, Nivelle issued an Order of the Day which ended with the now-famous line: Ils ne passeront pas! (They shall not pass!)[5]. Nivelle ordered the employment of a creeping barrage when the French made their initial counter-stroke on 24 October.[6] The artillery supporting the infantry focused more on suppressing German troops as opposed to destroying specific objects.[6] These tactics proved to be effective as Fleury was captured on 24 October, as well as Fort Douaumont, a building whose capture by the Germans on 25 February 1916 was highly celebrated in Germany.[7] Nivelle's successful counter-strokes were an important factor behind the decision to appoint him to become the commander-in-chief of the French armies on 12 December 1916.[2]

Nivelle believed that a large saturation bombardment, followed by an extensive creeping barrage and by aggressive infantry assaults, would be able to break the enemy's front defences and help his troops reach the German gun line during a single attack, which would be followed by a breakthrough within two days.[1] In 1917, Nivelle proposed that French forces should greatly attack the Germans on the Aisne-keeping 27 divisions in reserve to exploit the rupture of the German defences that was expected to occur as a result-after British and other French forces had launched preliminary attacks between Arras and the Oise to keep German reserve troops occupied.[1] Sir Douglas Haig, a British Field-Marshal, had reservations regarding Nivelle's plan, and supported it in general terms, and as long as planned British operations in Belgium were not curtailed.[1][4] Looking for an alternative to more months of attrition warfare, British and French political leaders supported Nivelle's proposal.[4] For this offensive, Haig would be subordinate to Nivelle.[8]

Between 16 March and 20 March 1917, the Germans withdrew from the Noyon salient and a smaller salient near Bapaume.[9] French General Franchet d'Esperey, commander of the Northern Army Group, asked Nivelle if he could attack the Germans as they withdrew.[9] Nivelle believed that that action would disrupt his operational plan, and refused d'Esperey's request as a result.[9] Nivelle has since been deemed to have missed his only real opportunity to disrupt the German withdrawal.[9] Haig's confidence in Nivelle's planned offensive did not improve when Paul Painlevé was appointed to become the French Minister of War in March 1917, as Painlevé had little faith in Nivelle's concepts.[10] Philippe Pétain, over whose head Nivelle had been promoted to become commander-in-chief, requested that he be allowed to launch a major attack against the Germans near Reims.[10] The proposal is considered to have likely resulted in considerable difficulties for the Germans, but Nivelle refused because he didn't want to risk delaying his offensive for the two weeks it would require to allow Petain to carry out his attack.[10] General Micheler, commander of the French Reserve Army Group, which was sidelined for the role of exploting the expected breakthrough on the Aisne, had serious misgivings about the upcoming battle, and in a letter sent to Nivelle on 22 March, Micheler argued that a breakthrough might not likely be able to occur as quickly as Nivelle wanted, as the Germans had reserves available, and had strengthened their defences along a sector of the Aisne which was important for the success of the French attack.[10] The other commanders of the French Army Groups also had concerns, but Nivelle did not make any major adjustments to his plan.[10]

Assisted by Colonel Messimy, a former French Minister of War, Micheler was able to communicate his worries to the French Prime Minister, Alexandre Ribot. On 6 April, a Council of War was held in Compiegne to discuss Nivelle's planned offensive, which was composed of Painlevé, Micheler, Petain, Nivelle, and French President Poincaré, as well as other French politicians. Painlevé argued that the Russian Revolution meant that France shouldn't expect any major help from Russia, and that the offensive should be delayed until the Americans could get involved. Micheler and Petain said that they doubted the French troops involved in the attack could penetrate the German defences beyond its second position, and suggested a more limited operation. Poincaré, summing up the discussions, said that the offensive should proceed, but that it should be halted if it failed to rupture the German front. At this point, Nivelle offered to resign, to see if he could call the bluff of his critics. The French politicians seemed unwilling to push matters that far, and declared that they had complete confidence in him. The Council of War, as a result of the politicians' appeasement of Nivelle, ended with the worries other French generals had about the offensive still existing, though their complaints did put Nivelle under greater pressure. On 4 April, during a German attack south of the Aisne, plans of the French assault for the offensive were reported to have been captured. Nivelle did not change his plans as a result.[10]

Nivelle Offensive

On 16 April 1917, the offensive, known as the Nivelle Offensive, was launched. It started a week after British forces had attacked near Arras. Nivelle made several declarations which improved the morale of the French troops involved in the Nivelle Offensive. Due to the facts that the preliminary bombardment against the Germans was markedly less effective than expected, and the lack of a sufficient number of French howitzers, the desired French breakthrough was not achieved on the first day of the operation, despite the use of 128 tanks. By 20 April, the French had 20,000 prisoners and 147 guns, which is considered to be "impressive results by the standards of previous years". However, a decisive breakthrough on the Aisne had not been achieved, the French had suffered 96,125 casualties by 25 April, the offensive had led to a shell shortage in France, the French medical services broke down, and the delay of transporting French wounded from the front-line was demoralising French soldiers.[11]

By the end of its first week, Nivelle's personal influence over the offensive had begun to reduce. Micheler convinced Nivelle to limit the scope of the offensive, with the objective now being to secure all of the Chemin des Dames ridge, and to gain control of Reims. Nivelle became increasingly depressed over the course of the offensive, as his orders were under a great degree of scrutiny by the French government. On 29 April, Nivelle's authority was undermined by the appointment of Petain to the position of Chief of the General Staff, as Petain effectively became the main military adviser to the government. Although the French were successful in securing parts of the Chemin des Dames during 4-5 May they were not sufficient to "repair Nivelle's crumbling reputation".[12]

After the Nivelle Offensive

When the offensive ended on 9 May, 187,000 French casualties had been sustained.[13] Although this was much less than the casualties in the Battle of Verdun, Nivelle had predicted a great success, and the country was bitterly disappointed.[13] Petain replaced Nivelle as Commander-in-Chief on 15 May.[13] In December Nivelle was sent to serve in Africa. He returned to France after the end of the First World War in November 1918, retiring from the military in 1921.[2] He died on 22 March 1924.

Legacy

Nivelle has come under a notable degree of criticism for some of his actions during the First World War. Julian Thompson contends that Nivelle was "careless of casualties"[14], that he was a "disastrous choice to succeed Joffre as Commander-in-Chief"[14], and that the planning for the Nivelle Offensive was "slapdash".[15] In the book World War 1: 1914–1918, the execution of the Nivelle Offensive is considered to have been "murderous".[16] David Stevenson says that the attack on the Chemin des Dames was a "disaster".[17]

Nivelle is also considered positively in some ways. In The Macmillan Dictionary of the First World War, he is described as "a competent tactician as a regimental colonel in 1914"[18], that his creeping barrage tactics were "innovative"[19], and that he was able to galvanize "increasingly pessimistic public opinion in France" in December 1916."[19] J Rickard believes Nivelle's push for a greater development of the tank contributed to its improvement by 1918, and he also says that Nivelle was a "gifted Artilleryman".[2]

The Nivelle Offensive is blamed by some historians for starting the French army mutinies of 1917. Tim Travers states that "the heavy French casualties of the Nivelle offensive resulted in French army mutinies"[20], and David Stevenson proposes that "the Nivelle offensive-or more precisely the decision to persist with it-precipitated the French mutinies of May and June [1917]".[21]

Decorations

- Légion d'honneur

- Knight (9 July 1895)

- Officer (21 December 1912)

- Commander (10 April 1915)

- Grand Officer (13 September 1916)

- Grand Cross (28 December 1920)

- Médaille militaire (30 December 1921)

- Croix de guerre 1914–1918 with 3 palms

- Médaille Interalliée de la Victoire

- Médaille Commémorative de l'expédition de Chine 1900–1901

- Médaille Commémorative du Maroc with agrafes "Oudjda" "Haut-Guir"

- Médaille Commémorative de la Grande Guerre

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium)

- Croix de guerre (Belgium)

- Officer of the Nicham Iftikhar (Tunisia)

- Distinguished Service Medal (US)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 105.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Rickard, J (20 February 2001). "Robert Georges Nivelle (1856–1924), French General". http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/people_nivelle.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 74.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 75.

- ↑ The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 77.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 78.

- ↑ The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 72.

- ↑ The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 107.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 112.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 119.

- ↑ The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 121.

- ↑ The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 122.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 The First World War: The War To End All Wars. p. 123.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 The 1916 Experience: Verdun and the Somme. p. 20.

- ↑ The 1916 Experience: Verdun and the Somme. p. 59.

- ↑ World War 1: 1914–1918. p. 82.

- ↑ 1914–1918: The History Of The First World War. p. 367.

- ↑ The Macmillan Dictionary of the First World War. p. 343.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 The Macmillan Dictionary of the First World War. p. 344.

- ↑ The Killing Ground: The British Army, The Western Front, & The Emergence Of Modern War 1900–1918. p. 256.

- ↑ 1914–1918: The History Of The First World War. p. 327.

Sources

- Simkins, Peter; Jukes, Geoffrey & Hickey, Michael, The First World War: The War To End All Wars, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-738-7

- Blake, Robert (editor); The Private Papers of Douglas Haig 1914–1918, London 1952

See also

- Battle of Verdun

- Nivelle Offensive

- Second Battle of the Aisne

- Philippe Pétain

- Chemin des Dames